Urban Shelves

Design Team: Michael Frederick, Yilip Kang, Francesco Valente-Gorjup, Aaron Thomsen | Advisors: Rodger Sherman

Los Angeles, California : 2009

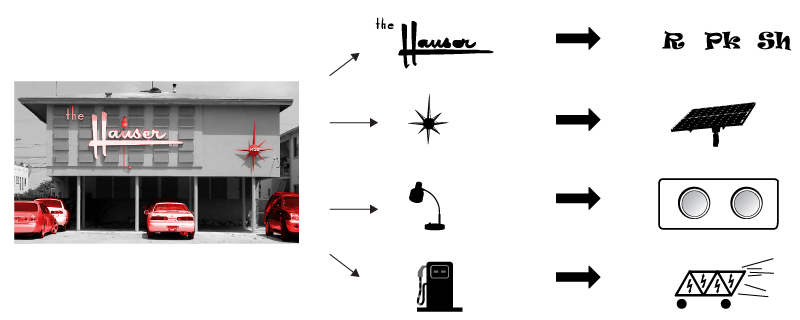

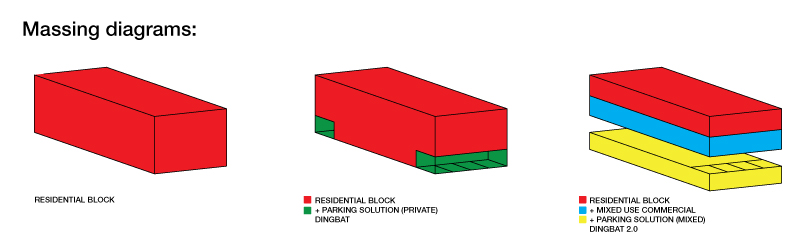

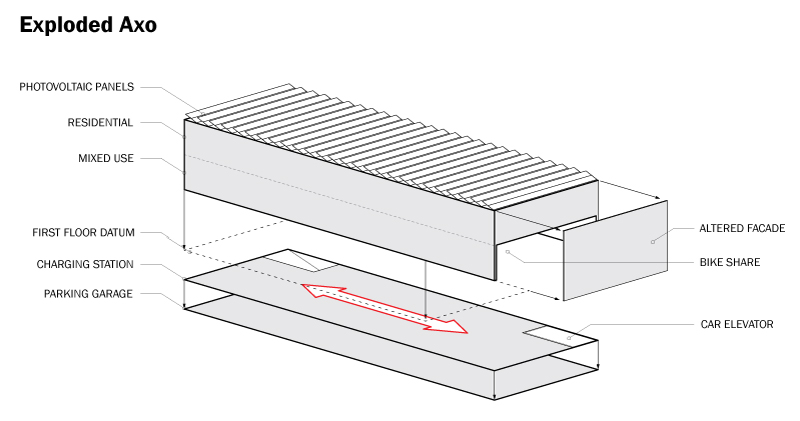

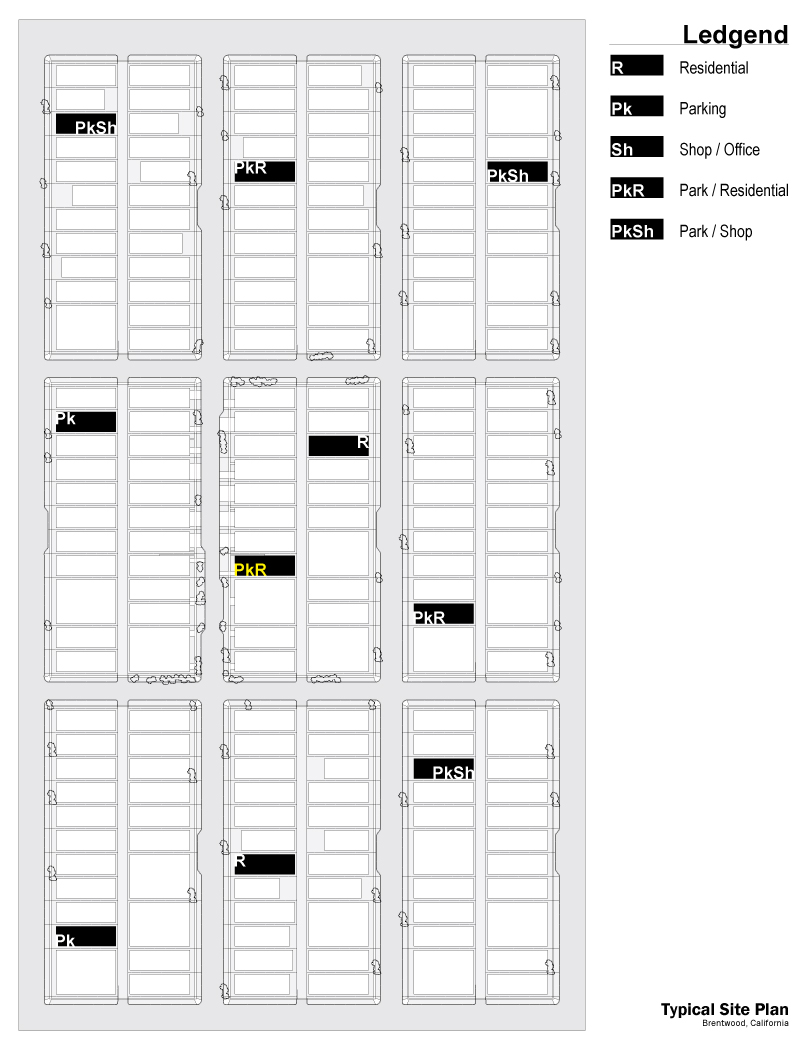

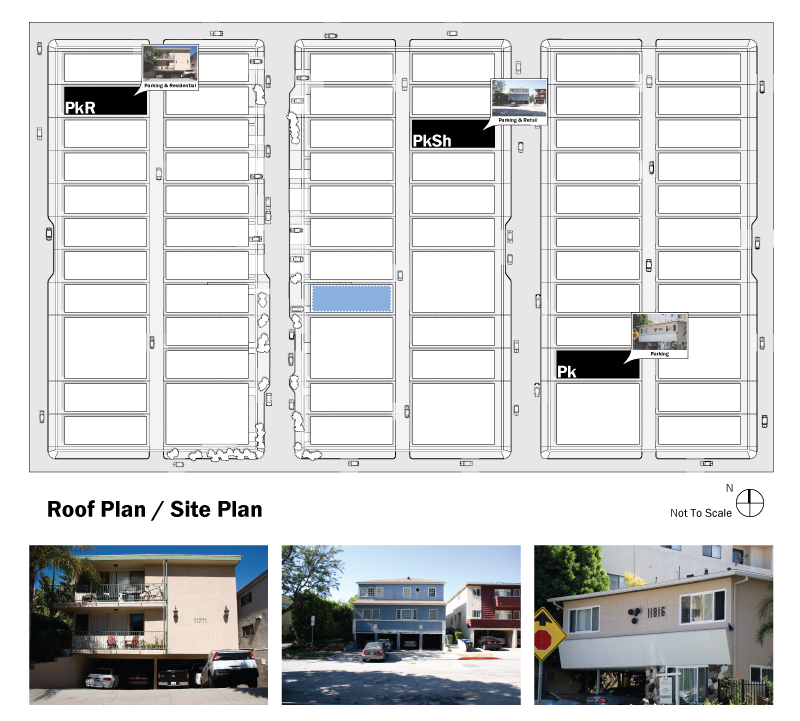

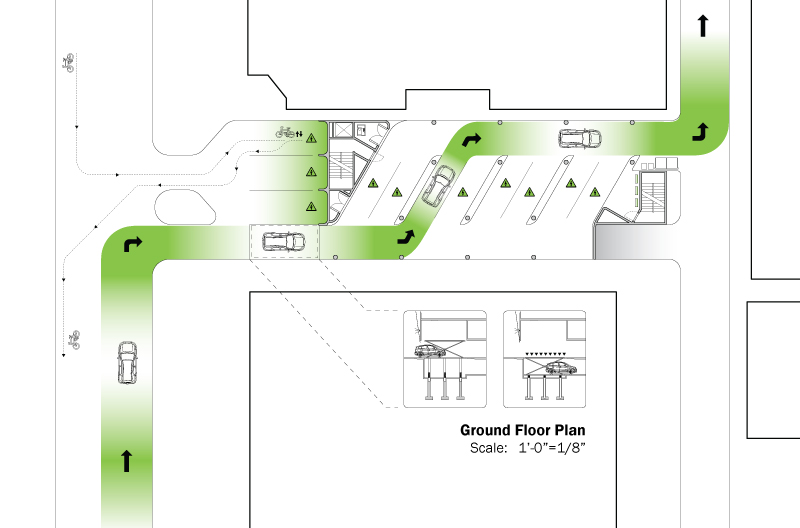

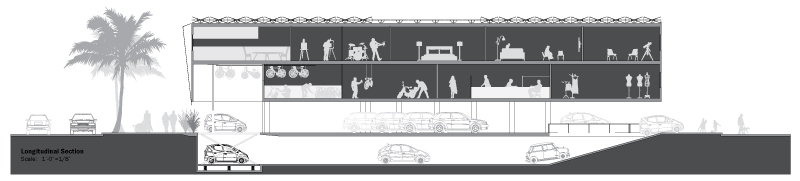

A dingbat is an ornament, character or spacer used in typesetting, sometimes more formally known as a “printer’s ornament” or “printer’s character”. In Los Angeles, however, the dingbat became a common building typology characterized by a relatively basic three story wood-frame structure, which houses several rental units. The defining characteristic of the dingbat is unquestionably its parking, which is awkwardly tucked under the overhang created by setting the ground floor back from the front façade to accommodate several vehicles. Other noticeable traits of the dingbat are: the use of an ornate font on its façade to indicate the address, a light or lantern, as well as a type of ornament, which is usually in the shape of star. Today dingbats are still seen in many L.A. neighborhoods but suffer on the real-estate market because of their peculiar parking-oriented design that ends up ruining the façade, making the public front of these otherwise lovely dwellings bleak and uninviting. In order to make the dingbat more integrated into the urban fabric and infrastructure as well as more sustainable and aesthetically appealing the new dingbat decided to take inspiration from the old’s primary raison d’etre: parking. Our first move was to completely remove any units from the ground floor, allowing this space to be used as a recharging station for electric vehicles. The energy for recharging the vehicles would come from heliostatic photovoltaic roof. This station would be one of many located in the neighborhood and would be open to anyone driving an electric car. The traditional dingbat light would be replaced by a light indicating the availability of a charging spot. Parking for residents as well as rentable spaces would be located underground and made accessible by a gravity operated car elevator. Both the charging lot as well as the parking lot would ideally generate enough income to allow for subsidized housing and non-profit organizations, such as bike shares, to inhabit the remaining two floors of the dingbat. In fact, in the front of the new dingbat there would be an automated dispenser for renting bicycles in order to promote a more sustainable means of transportation. The intention is to largely maintain the key elements of the dingbat, but to adapt them to the new demands of the dingbat’s modified program. What emerges is a sensible twist on an L.A. classic that has been imbued with new life and brought up to date with the demands and possibilities of multi-use buildings, which belong to an increasingly problematic urban fabric and infrastructure.